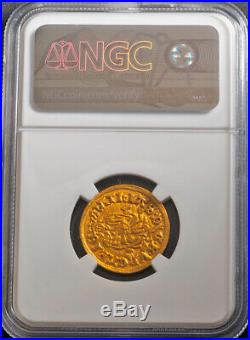

1490, Hungary, Matthias Corvinus. Gold Ducat Coin. Nagybanya mint! NGC MS-61

Certified and graded by NGC as MS-63! Mint Place: Nagybanya (today´s Baia Mare in Romania) Reference: Friedberg 22, Huszar 680, Leng.

Denomination: Gold Ducat (also known as Gold Gulden in German or Aranyforint in Hungarian). Diameter: 21mm Weight: 3.61gm Material: Gold!

Obverse: Crowned and haloed figure of Saint Ladislaus standing facing with battle-axe and globus cruciger. Privy marks (n/coat-of-arms) in fields. Legend: S · LDISL AVS · RX Reverse: Crowned and togate figure of the Virgin Maria (Madonna), holding baby-Jesus child. Thistles at sides, a raven with a ring in beak below. Legend: mThIS · D (raven with ring in beak) G · R · VnGARI.

1040 29 July 1095 was King of Hungary from 1077 until his death, "who greatly expanded the boundaries of the kingdom and consolidated it internally; no other Hungarian king was so generally beloved by the people". Before his ascension to the throne, he was the main advisor of his brother, Géza I of Hungary, who was fighting against their cousin, King Solomon of Hungary. When his brother died, his followers proclaimed Ladislaus king according to the Hungarian tradition that gave precedence to the eldest member of the royal family to the deceased king's sons. Following a long period of civil wars, he strengthened the royal power in his kingdom by introducing severe legislation.

He also could expand his rule over Croatia. After his canonisation, Ladislaus became the model of the chivalrous king in Hungary.23 February 1443 6 April 1490 also called. Was King of Hungary from 1458, at the age of 14 until his death. After conducting several military campaigns he became also King of Bohemia, (14691490) and Duke of Austria. Matthias was born in Kolozsvár in the Kingdom of Hungary (today Cluj-Napoca, Romania) in a house now known as the Matthias Corvinus House.

He was second son of John Hunyadi, a successful Hungarian General of Romanian descent who had risen through the ranks of the nobility to become regent of Hungary. Matthias' mother was Erzsébet Szilágyi, from a Hungarian noble family. His tutors were the learned János Vitéz, bishop of Nagyvárad, whom he subsequently raised to the primacy, and the Polish humanist Gregory of Sanok. The precocious Matthias quickly mastered German, Italian, Romanian, Latin and principal Slavic languages apart from his native Hungarian, frequently acting as his father's interpreter at the reception of ambassadors. His military training proceeded under the eye of his father, whom he began to follow on his campaigns when only twelve years of age.In 1453 he was created count of Beszterce, and was knighted at the siege of Belgrade in 1456. The same care for his welfare led his father to choose him a bride in the powerful family of the Counts of Cilli. Mattias was married to Elizabeth of Celje. She was the only known daughter of Ulrich II of Celje and Catherine Cantakuzina. Her maternal grandparents were Ðurad Brankovic and Eirene Kantakouzene.

But the young Elizabeth died in 1455, before the marriage was consummated, leaving Matthias a widower at the age of fifteen. After the death of Matthias's father, there was a two-year struggle between Hungary's various barons and its Habsburg king, Ladislaus the Posthumous (also king of Bohemia), with treachery from all sides. Matthias's older brother László Hunyadi was one party attempting to gain control. Matthias was inveigled to Buda by the enemies of his house, and, on the pretext of being concerned in a purely imaginary conspiracy against Ladislaus, was condemned to decapitation, but was spared on account of his youth.

In 1457, László Hunyadi was captured with a trick and beheaded, while the king died suddenly in November that year; rumors of poisoning were dispelled by research in 1985 which gave acute leukemia as the cause of death. Matthias was taken hostage by George of Podebrady, governor of Bohemia, a friend of the Hunyadis who aimed to raise a national king to the Magyar throne. Podebrady treated Matthias hospitably and affianced him with his daughter Catherine, but still detained him, for safety's sake, in Prague, even after a Magyar deputation had hastened thither to offer the youth the crown. Matthias took advantage of the memory left by his father's deed, and by the general population's dislike of foreign candidates; most the barons, furthermore, considered that the young scholar would be a weak monarch in their hands. An influential section of the magnates, headed by the Palatine László Garai and by Miklós Újlaki, voivode of Transylvania, who had been concerned in the judicial murder of Matthias's brother László, and hated the Hunyadis as semi-foreign upstarts, were fiercely opposed to Matthias's election; however, they were not strong enough to resist against Matthias's uncle Mihály Szilágyi and his 15,000 veterans.

Thus, on 20 January 1458, Matthias was elected king by the Diet. This was the first time in the medieval Hungarian kingdom that a member of the nobility, without dynastic ancestry and relationship, mounted the royal throne. Such an election upset the usual course of dynastic succession in the age. In the Czech and Hungarian states they heralded a new judiciary era in Europe, characterized by the absolute supremacy of the Parliament, (dietal system) and a tendency to centralization. At this time Matthias was still a hostage of George of Podebrady, who released him under the condition of marrying his daughter Kunhuta (later known as Catherine).

On 24 January 1458, 40,000 Hungarian noblemen, assembled on the ice of the frozen Danube, unanimously elected Matthias Hunyadi king of Hungary, and on 14 February the new king made his state entry into Buda. Matthias was 15 when he was elected King of Hungary: at this time the realm was environed by perils. The Ottomans and the Venetians threatened it from the south, the emperor Frederick III from the west, and Casimir IV of Poland from the north, both Frederick and Casimir claiming the throne. The Czech mercenaries under Giszkra held the northern counties and from thence plundered those in the centre. Meanwhile Matthias's friends had only pacified the hostile dignitaries by engaging to marry the daughter of the palatine Garai to their nominee, whereas Matthias refused to marry into the family of one of his brother's murderers, and on 9 February confirmed his previous nuptial contract with the daughter of Podebrady, who shortly afterwards was elected king of Bohemia (2 March 1458).

Throughout 1458 the struggle between the young king and the magnates, reinforced by Matthias's own uncle and guardian Szilágyi, was acute. He recovered the Golubac Fortress from the Ottomans, successfully invading Serbia, and reasserting the suzerainty of the Hungarian crown over Bosnia. In the following year there was a fresh rebellion, when the emperor Frederick was actually crowned king by the malcontents at Vienna-Neustadt (4 March 1459); Matthias however drove him out, and Pope Pius II intervened so as to leave Matthias free to engage in a projected crusade against the Ottomans, which subsequent political complications, however, rendered impossible. On 1 May 1461, the marriage between Matthias and Podebrady's daughter took place.

From 1461 to 1465 the career of Matthias was a perpetual struggle punctuated by truces. Having come to an understanding with his father-in-law Podebrady, he was able to turn his arms against the emperor Frederick.

In April 1462 the latter restored the holy crown for 60,000 ducats and was allowed to retain certain Hungarian counties with the title of king; in return for which concessions, extorted from Matthias by the necessity of coping with a simultaneous rebellion of the Magyar noble in league with Podebrady's son Victorinus, the emperor recognized Matthias as the actual sovereign of Hungary. Only now was Matthias able to turn against the Ottomans, who were again threatening the southern provinces.He began by defeating the Ottoman general Ali Pasha, and then penetrated into Bosnia, capturing the newly built fortress of Jajce after a long and obstinate defence (December 1463). On returning home he was crowned with the Holy Crown on 29 March 1464. Twenty-one days after, on 8 March, the 15-years-old Queen Catherine died in childbirth.

The child, a son, was stillborn. After driving the Czechs out of his northern counties, he turned southwards again, this time recovering all the parts of Bosnia which still remained in Ottoman hands.Matthias gained independence of and power over the barons by dividing them, and by raising a large royal army. (the King's Black Army of Hungary of mercenaries), whose main force included the remnants of the Hussites from Bohemia. At this time Hungary reached its greatest territorial extent of the epoch (present-day southeastern Germany to the west, Dalmatia to the south, Eastern Carpathians to the east, and southwestern Poland to the north).

Soon after his coronation, Matthias turned his attention upon Bohemia, where the Hussite leader George of Podebrady had gained the throne. In 1465 Pope Paul II excommunicated the Hussite King and ordered all the neighbouring princes to depose him. On 31 May 1468, Matthias invaded Bohemia; however, as early as 27 February 1469, he anticipated an alliance between George and Frederick by himself concluding an armistice with the former. On 3 May the Bohemian Catholics elected Matthias king of Bohemia, but this was contrary to the wishes of both pope and emperor, who preferred to partition Bohemia.George however anticipated all his enemies by suddenly excluding his own son from the throne in favour of Ladislaus, the eldest son of Casimir IV, thus skillfully enlisting Poland on his side. The sudden death of Podebrady in March 1471 led to fresh complications. He suppressed this domestic rebellion indeed, but in the meantime the Poles had invaded the Bohemian domains with 60,000 men, and when in 1474 Matthias was at last able to take the field against them in order to raise the siege of Breslau, he was obliged to fortify himself in an entrenched camp, whence he so skillfully harried the enemy that the Poles, impatient to return to their own country, made peace at Breslau (February 1475) on an. Basis, a peace subsequently confirmed by the congress of Olomouc (July 1479). During the interval between these peaces, Matthias, in self-defence, again made war on the emperor, reducing Frederick to such extremities that he was glad to accept peace on any terms.

By the final arrangement made between the contending princes, Matthias recognized Ladislaus as king of Bohemia proper in return for the surrender of Moravia, Silesia and Upper and Lower Lusatia, hitherto component parts of the Bohemian monarchy, till he should have redeemed them for 400,000 florins. The emperor promised to pay Matthias a huge war indemnity, and recognized him as the legitimate king of Hungary on the understanding that he should succeed him if he died without male issue, a contingency at this time somewhat improbable, as Matthias, only three years previously (15 December 1476), had married his third wife, Beatrice, daughter of Ferdinand I of Naples. The emperor's failure to follow through on these promises induced Matthias to declare war against him for the third time in 1481. The Hungarian king conquered all of the fortresses in Frederick's hereditary domains. Finally, on 1 June 1485, at the head of 8,000 veterans, he made his triumphal entry into Vienna, which he henceforth made his capital.

Styria, Carinthia and Carniola were next subdued; Trieste was only saved by the intervention of the Venetians. Matthias consolidated his position by alliances with the dukes of Saxony and Bavaria, with the Swiss Confederation and the archbishop of Salzburg, establishing henceforth the greatest potentate in central Europe. In 1471 Matthias renewed the Serbian Despotate in south Hungary under Vuk Grgurevic for the protection of the borders against the Ottomans. In 1479 a huge Ottoman army, on its return home from ravaging Transylvania, was annihilated at Szászváros (modern Orastie, 13 October 1479) in the so-called Battle of Breadfield. The following year Matthias recaptured Jajce, drove the Ottomans from northern Serbia and instituted two new military banats, Jajce and Srebernik, out from reconquered Bosnian territory.

In 1480, when an Ottoman fleet seized Otranto in the Kingdom of Naples, at the earnest solicitation of the pope he sent the Hungarian general, Balázs Magyar, to recover the fortress, which surrendered to him on 10 May 1481. Again in 1488, Matthias took Ancona under his protection for a while, occupying it with a Hungarian garrison. On the death of sultan Mehmet II in 1481, a unique opportunity for the intervention of Europe in Ottoman affairs presented itself. A civil war ensued in Ottoman Empire between his sons Bayezid and Cem; the latter, being worsted, fled to the knights of Rhodes, by whom he was kept in custody in France. Matthias, as the next-door neighbour of the Ottomans, claimed the custody of so valuable a hostage, and would have used him as a means of extorting concessions from Bayezid.

But neither the pope nor the Venetians would accept such a transfer, and the negotiations on this subject greatly embittered Matthias against the Papal court. The last days of Matthias were occupied in endeavouring to secure the succession to the throne for his illegitimate son John; Queen Beatrice, though childless, fiercely and openly opposed the idea and the matter was still pending when Matthias, who had long been crippled by gout, expired very suddenly on 6 April 1490, just before Easter. At times Matthias had Vlad III the Impaler, Prince of Wallachia, as his vassal.Although Vlad had great success against the Ottoman armies, the two Christian rulers disagreed in 1462, leading to Matthias imprisoning Vlad in Buda. However, wide-ranging support from many Western leaders for Vlad III prompted Matthias to gradually grant privileged status to his controversial prisoner. Vlad was eventually freed and married Matthias' cousin, Ilona Szilagy. As the Ottoman Empire appeared to be increasingly threatening as Vlad Tepes had warned, he was sent to reconquer Wallachia with Hungarian support in 1476. Despite the earlier disagreements between the two leaders, it was ultimately a major blow to Hungary's status in Wallachia when Vlad was assassinated that same year.

In 1467, a conflict erupted between Matthias and the Moldavian Prince Stephen III, after the latter became weary of Hungarian policies in Wallachia and their presence at Kilia; added to this was the fact that Matthias had already taken sides in the Moldavian conflicts preceding Stephen's rule, as he had backed Alexandrel and, possibly, the ruler referred to as. Stephen occupied Kilia, sparking Hungarian retaliation, that ended in Matthias' bitter defeat in the Battle of Baia in December (the King himself is said to have been wounded thrice). The item "1490, Hungary, Matthias Corvinus. NGC MS-61" is in sale since Tuesday, September 15, 2020. This item is in the category "Coins & Paper Money\Coins\ World\Europe\Hungary".

The seller is "coinworldtv" and is located in Wien. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Composition: Gold

- Country/Region of Manufacture: Hungary

- Certification: NGC

- Grade: MS 61